They eventually reach a ‘solitary little farmhouse which has made a scanty clearing in the moor’. Strephon includes some wonderful detail about the old lady who lived there, worrying about her husband walking home after taking too much ale:

“The ancient dame is crooning alone, ‘John’ – the sharer of her years – ‘has gone to Boxton to pay th’ rent to th’ Duke’, and she is fretful that he will be ‘coming whoam full up wi’ yell which’ll do his rheumatics a power o’harm.’ And she puffs away silently at the consoling pipe.”

Hie to haunts right seldom seen,

Lovely, lonesome, cool, and green.

SCOTT

It all came about through Somebody – a sweet symphony in real-skin – losing a skate strap.

The discovery of the loss – as paradoxical an expression by the way, as the “If I am found, then I am lost!” ejaculation of the haunted fugitive in the melo-drama – was made when we were approaching to the Reservoir that supplies the Engine House on the High Peak Railway at Bunsal Cob.

We had walked from Buxton along the Manchester Road – a distance of three miles – with the intention of cutting our initials on the ice. “Have you ever seen the Goyt Valley in the depth of winter?” asked this bonny little maiden, the keen air heightening the beauty of her face with an unwonted colour.

“I have not even seen the Valley in summer.” I was fain to confess, ashamed of my own ignorance.

“Then you shall make its acquaintance this afternoon.” She said with a matronly air of decision. “It is an old and favourite friend of mine, and if you don’t thank me for giving you an introduction, I will”

But no matter. The threat was an idle one, and we chatted away merrily. We didn’t say anything clever, or poetical, or aesthetic; we posed in no attitudes of romantic admiration; and I am apprehensive that if our careless talk came to be coldly analysed it would be proved great rubbish.

But the happiness of life, my friend, is not made of heroics. It consists largely of little things; it is composed of trifles. And that afternoon we were both as happy as I daresay we ever shall be in this mundane sphere. But to return to that bright time.

It is a beautiful day at the end of November. That misanthropical month, so associated with drizzle and fog, has at Buxton redeemed its bad character by giving us a bright blue sky, and a thin clear air that must be very trying to the able-bodies poor, since it trebles one’s appetite, and gives the genus homo a whole series of stomachs, like the cow.

At a time when London, and Manchester are choking with fogs that might be blasted with dynamite, Buxton – a thousand feet above the mud and mist – has an elastic, lucent air that braces the nerves and when the perverse east wind is making everybody peevish, the residents of this Derbyshire Spa are barricaded at every approach by barriers of determined hills from the assaults of the bronchitis-dealing blast; while the scenery of the Peak in winter has charms of which few people have any conception.

For that matter, nature is as beautiful in her winter appearance as in her summer aspect. It seems so to my eyes, and Somebody emphasizes my opinion with her endorsement, of course the charm is a different one.

It is as distinct as the sunny light diaphanous muslin of Somebody in July, with bright flowers jewelling bosom and hat, is from the soft dark furs of that vivacious young lady in January. But there is a charm, nevertheless, just as there is one glory of the sun, another of the moon, and another of the stars.

The picturesque side of winter has been neglected by painters. They represent Nature in Art only as seen six months out of twelve. Then out-door landscape painting is a more luxurious occupation.

In literary description the same one-sided practice prevails. Somebody protests that nearly all the pen-pictures of Derbyshire scenery which she has read have commenced: “It was a bright June morning;” or “The time was merrie month of May;” or “The fair scene lay in the languid sunshine of sultry July.”

“As if,” she said, “there was no beauty about hills and valleys, no attraction in the moorland steppes, no grandeur in the tempestuous sunsets and twilights and cloud shadows of winter.

“As if men were so many dormice, and hibernated through the artistic winter months, when there is a sharpness of outline and a tenderness of colour on the hills, and a fresh elasticity in the air, which are lost in the heat and haze of summer.”

All this she argued with an earnestness that became really eloquent by its manner, by the witching animation of eye and the musical inflexion of voice, denied masculine orators from Demosthenes to Victor Hugo.

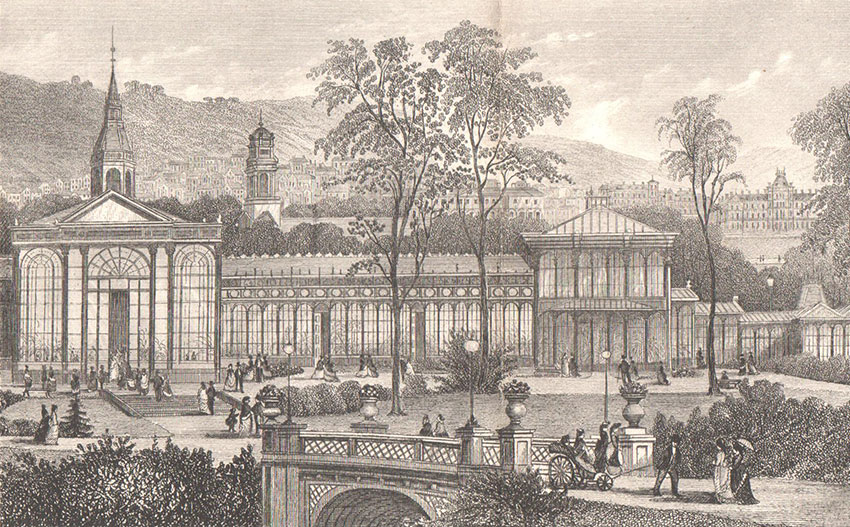

And yet Buxton is empty. The stray visitor monopolises the whole of the light, buoyant air of the place. Standing in the shadow of the Crescent, he is as much alone as if he were in the vast solitudes of Sahara, and he feels like a second-hand Marius, contemplating the desolation of a fashionable Carthage.

The properties of the hotels are dining with each other to make up a table for dinner. They would, I verily believe, bribe a visitor just now for the curiosity of his patronage, unless in the process of treaty, the said visitor shared the fate of Actieon, and had his dirjecta membra strewn along the Colonnade by competitive waiters tearing him in pieces in jealous rivalry.

Some day, some celebrated person will suddenly discover what a delightful winter residence Buxton really is, just as Lord Brougham made Cannes by believing that that place agreed with him. Then it will become fashionable to repair to Buxton from October to March, and lodgings will be at a premium.

It’s at the top of the Bunsal Incline and many visitors to the Goyt Valley will pass it on their way to the twin reservoirs.

It once provided water to power the steam-driven pulleys which pulled trains up and down the steep slope.

The atmosphere has the rich softness of a Claude landscape. There is such a golden mellowness in the November sunshine that the afternoon seems to swim under the lemon sky; across the ice, virgin white, save where some frozen-out labourers have swept broad black rings for skating, the westering sun, a ruddy copper shield, shines with a red horizontal light across wild tracts of hilly moors, with just a suggestion of snow relieving their somber shade.

There are great hollows in the moors, and there is an intersecting space between the hills which tells of a deep valley. Not a tree, Not a house. The only other object in the landscape, from the point whence our mental camera now focuses it, is the tall chimney of the solitary engine house of the High Peak Railway, a mineral line whose rails wind round miraculous curves and up extravagant gradients through Undiscovered Derbyshire, from Whatstandwell to Whaley Bridge.

But the foreground of the picture is filled with a merry-moving steel-shod multitude, mostly Buxton residents, all mixed up in kaleidoscopic combinations, the patches of cardinal about the hats and throats of the girls, giving just the warm tints which a painter would distribute in the grouping.

The captivating swing of that tall lissome lass now swiftly curving yonder, with the sun glancing on the blades of her skates, is one of the most graceful sights possible; for a handsome English maiden skating makes really a fine picture, as stately as the pose of a swan, or the movement of a yacht.

Somebody is delighted with two bright-eyed girlettes – vignettes in black velvet and chocked stockings – who are being taken in tow across the ice by a big St. Bernard dog, and it would be difficult to say which most enjoys the fun: the harnessed animal or the two bonnie weans.

That is their brother learning to strike out, and tumbling down very often. But, bless you, he never seems satisfied with the frequency of his falls, and is adding to their number, when Somebody, nudging my elbow, says: “We are not stationary engines, and I must really remind you that our exploration will involve some walking.”

Without being tediously topographical, I may remark that the valley of the Goyt is approached from Bunsall by a road called Goyts Lane. A rough declivitous road, more like the dry bed of a bygone mountain torrent, than the carriage way it claims to represent.

Heath, cranberry, bilberry, and wortleberry infringe on either side, and sometimes dispute the possession of the road with the traveler altogether. The bilberry leaves are a vivid green among the prevailing neutral tints.

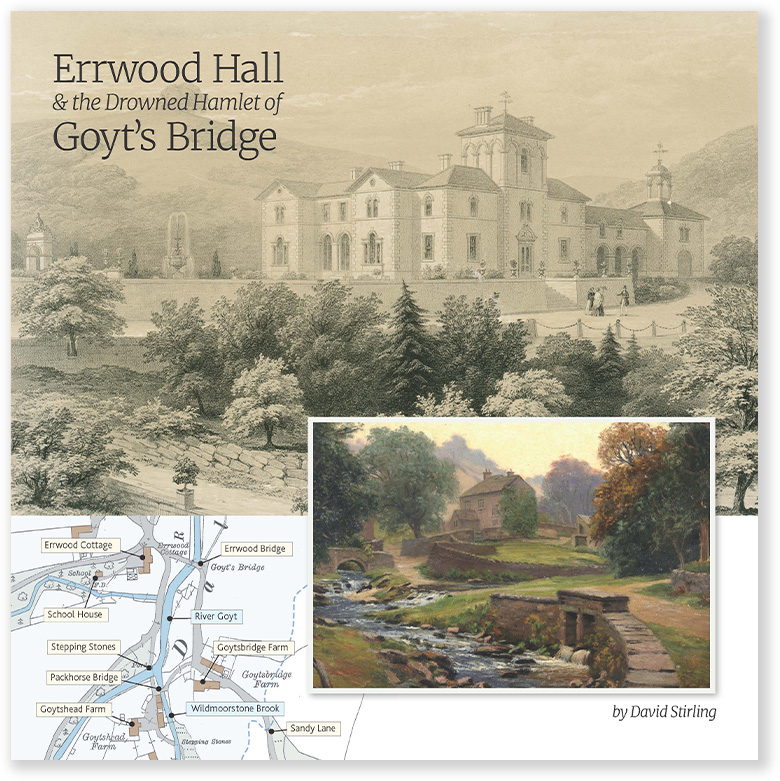

Presently comes a glimpse of firs and larches, pine and spruce, on the bank rising out of the valley, and now behold! There is Goyts Bridge: a wooded hollow amid the meeting of waters. There is a grey farmhouse, and here and there the blue film rises from a cottage mixed up in dark patches of pine and fir.

This important crossing point is all that remains of Goyt’s Bridge. It was saved and moved further upstream in the mid ’60s, before the valley was flooded.

Click here for more information about the bridge.

I must talk seriously to Somebody about Political Economy.

At Goyts Bridge, the road to the right leads to Errwood Hall, to which Somebody is wishful to take her charge another day. Our present path is that to the left, and follows up the river as it runs away from its mountain home.

The spot is musical with the meeting of waters. A grey stone arch spans a tinkling tributary; there is an old cottage, with an interior like a bit of Tenier’s; together with a picturesque blending of swift water, projecting rock, and hanging tree, that might be a scene specially “set” by Nature for a stage-picture.

There is not in the wild world a valley so sweet,

As that vale in whose bosom the bright waters meet;

Oh! The last rays of feeling and life must depart.

Ere the bloom of that valley shall fade from my heart.

So carols Somebody, who has already forgotten all about the millocracy of New Mills and Stockport. For we are now in the deep canon, pursuing a narrow path that rises and falls and skirts small precipices. And which of us will first forget that sudden vision of a long vista of valley, seen under a cold lemon sky, with the eager voiceful river breaking over a tumult of mossy boulders in a thousand white waterfalls, and here and there catching a tinge of red from the frosty sun?

At the bank-sides, where the current is not swift, the water is frozen, and little tributary water-threads have a surface of thin clear ice under which we see the water moving like quicksilver.

There are icicles on the grey lichened rocks, and crystals of snow shine on the roadway, which winds high above the torrent. The dark-limbed trees are brought out in sharp relief by the white rime of hoar-frost, feathery, fantastic, lace-like; and the needles of the firs are coated with shining crystals.

But the light covering of rime and snow cannot hide the carpet of faded oak, and copper beech, and broad Spanish chestnut leaves, which lie ankle deep in heaps of red and brown and yellow.

There is scarcely any foliage left on those trees, but on either bank soldierly rows of dark green fir and pine and larch are drawn up in line to salute the river as it passes in hasty review. On the hazel are threads of scarlet; a few red haws remain on the hawthorn; and there is the plum-like bloom of the black sloe.

But for the ceaseless song of the river – now soft and tender in a minor key, like a lover’s entreating whisper; now a sweet lullaby, with a note of sadness in it, sung to the silent and listening rocks, as the water reposes in contemplative pools that mirror bits of sky; then a gay careless shout, a loud defiant laugh, as it wakens from its reflective mood and dashes in restless madcap race heedlessly past lichened rocks and stretched-out arms of compassionate trees that try to stop its fight; – but for this voiceful water, I say, absolute silence would reign in the valley.

Frost and snow hold Nature is quiet restraint. We have seen, it is true, the robin and the tom-tit; once there has come the sceap-sceap of a snipe rising in zig-zag flight, with breast as brown as the fallen chestnut leaves; once the missel-thrush has shown his spotted chest; once we have caught sight of the golden bill of the blackbird.

There are the footprints of rabbits and hares; we hear the hollow note of the wood-pigeon; and Somebody says that she has seen the heron sitting watchful and weird by the water when the gloom has been gathering in this wild solitude.

And now the aspect of the valley is altered. The trees cease, the bronzed moors rise precipitously from the stony bed of the stream, and encompass it on either hand.

Presently, to our right, are one or two houses that seem to make the solitude all the more lonely. The sun has insensibly gone down, and there is a metallic twilight. The glimmer of a candle shines in one of the ghostly cottage windows.

Close by is an old gritstone quarry, which has a story that belongs to the romance of trade. It was first worked by the originator of parcel-vans, the Pickford whose name is as familiar to us as Her Majesty’s face on pence and postage stamps.

That was when the present century was young. The flagstones which paved the Regent Street of those days were hewn from this quarry. They were carted all the way to London, via Leek, Bridgewater had not then conceived his water-highways, and George Stephenson, in his pitman’s clothes, was learning to read and write for fourpence a week at a night-school.

But canals came to be made, and railways were constructed, and it became no longer profitable to pave Piccadilly from the Peak. The supply of stone in this quarry is by no means exhausted, but the cost of carriage renders its working no longer profitable.

Time, which deals gently with most wounds, has healed the scars the quarrymen of a past generation inflicted on the cliff, and with lichen and ivy, fern and foliage and flowers, has lovingly repaired the ruin caused years ago.

And now we leave the river-side and strike across the moors. We are alone on the top of the world. The moon looks down upon us with pale steadfast gaze; the stars regard us with a thousand eyes. The road shows wan in the wide space of encompassing moor.

A far off group of gloomy pines stand-ghost-like in the white light. The only sound is caused by the plaintive cry of that bird of triple name – lapwing, peewit, plover. Once, too, the curlow – “the Whaup” of William Black’s “Daughter of Heth” – rise with its sharp wings in swift flight, with a shrill call with a roll in it, just like a pea-whistle.

But this stood at Derbyshire Bridge (it’s now the Park Rangers Centre). Our companions took a short cut across the moorland to reach the road – so would have just missed it.

I thought it was too good to be true to find an illustration of the same house – and covered in snow!

She says: “I sometimes think that to be in the middle of a moor under the stars is to experience more spiritual feeling than is induced in the solemnest cathedral or by the most earnest sermon.”

It appears that she knows the people at the house whose yellow window, in the broad space of mysterious moor, shows like a lighthouse gleam in mid-ocean.

An old woman, with a white mobcap – something like what the fashionable ladies of aesthetic South Kensington are reviving to-day – sits in the ingle-nook smoking a clay pipe of marvellous colouring.

There is a smell of peat about the fire; the only pictures on the walls are in the shape of substantial sides of bacon; there is a cheese knife on the table fashioned out of the old broad-sword of a cavalier.

The ancient dame is crooning alone, “John” – the sharer of her years – “has gone to Boxton to pay th’ rent to th’ Duke”, and she is fretful that he will be “coming whoam full up wi’ yell which’ll do his rheumatics a power o’harm.” And she puffs away silently at the consoling pipe.

And Somebody, with a tender consideration for the weakness of old people, quietly prompts me to leave the whole contents of my own poach to solace the old lady’s hours. It is one of the aged dame’s boasts that she has never slept out of that house for over fifty years. Half a century spent in vegetation.

To the dwellers in busy towns, who crowd so much experience and so many sensations into each day, these isolated hill people do not seem to live. The number of their days is longer than ours, and the days are longer, but one day is so much like another, that their existence is only a monotonous routine of food and sleep, a slow process of going to the grave. They do not really feel the pulse of life.

They from to-day and from to-night

Expected nothing more

Than yesterday and yester night

Had proffered them before.

And yet, perhaps, these simple dull quiet people are happier in their lives than we, with our daily discontent and fever fret.

The moon shines on the waves of moorland in a long path of white light, just as it does on the sea, making, as it seems, a silver road upon which you might walk up to the entrance of Heaven.

But what is that strange object in front of us standing out in sharp silhouette between moon and stars? It is a man, but his steps over the rough uneven way are very erratic. He is walking in figures of eight.

The old lady in the lonely farm yonder was quite right in her sorrowful apprehensions. It is “John,” and he is, indeed, “full up w’yell.” He is made more grotesque by a number of parcels – for he has been shopping – which, he being unable to carry, are tied all over his body.

We console with him about his rheumatics; and his efforts to balance himself in a dignified perpendicular position of attention are as broadly comic as a farce. “Oimunna stop and talk or Oi shall set,” he says at last, and the honest old man stumbles on, paying his attention to both sides of the moor.

The path across the moor brings us on to the Macclesfield road just above Burbage, where we are a mile from Buxton, whose gas lamps in the hollow strike strange to eyes which have grown accustomed to the sharp lights and dark shadows of the moors. When we get back to the town, we have walked altogether about eight or nine miles.

The exercise and the air have given us appetites that are Homeric in their greatness, and the old-fashioned knife-and-fork tea in the snugly-curtained room, with its glowing fire and wax candles, is not the least acceptable sensation on the day.

And afterwards Somebody is not too tired for music. And has she, perhaps, a lingering vision in her memory of that deep, still, beautiful, secluded valley of the afternoon, where a dozen rivulets and rills join their young voices in a perpetual hymn, which only the bending trees and the grand old hills are privileged to hear, when and sings;

Sweet vale of Avoca! how calm could I rest

In thy bosom of shade, with the friends I love best,

Where the storms that we feel in this cold world should cease,

And our hearts, like thy waters, be mingled in peace.

The route

*From Buxton, Strephon and his ‘Somebody’ lady companion walked up the ‘Long Hill’ road towards Whaley Bridge before turning left down Goyt’s Lane and following it all the way into Goyt’s Bridge. After crossing the packhorse bridge, they turn right over the stepping stones, then immediately left to follow the narrow lane towards Derbyshire Bridge. After passing Goytsclough, they cross over the Goyt and follow a footpath over the moors until they reach the old Macclesfield to Buxton road. This takes them all the way back into town. (I’ll try to recreate this walk – as far as possible – in the near future.)