The waterwheel would have been behind the slope to the right. (Click here for more on the cottages.)

My thanks to Mike for forwarding this article he discovered, published in the Buxton Advertiser on 19th December 1857. It answers a lot of my questions about the waterwheel at Goytsclough, which was reputed to be the second largest in the world. (View previous post.)

The writer explains that it was first used to scour paving stones – until the quarry closed. And then reused to crush stone and extract a mineral used in paint manufacture. (The article was written soon after the paint mill opened.)

The article disproved most of my assumptions about the waterwheel. But that’s not unusual! See bottom of post for details.

A ramble to the ‘improvements’ at Goyt’s Clough

One of the most agreeable duties connected with this journal is the recording of improvements and changes which cannot fail to influence beneficially the prosperity and general welfare of the town and neighbourhood; and thus we love to chronicle every step of progress – short strides as well as long ones.

Having heard that Goyt’s Clough was showing signs of returning animation, we were tempted forth, in the afternoon of one of those many fine, warm, bright sunny days which have latterly gladdened the hills, to ramble thither and judge for ourself.

Many readers of these pages, are ignorant of the locality of Goyt’s Clough, know it only by name, or never heard of it before. It is too much the custom to “Keep on the Walks,” to contine your rambles to the Gardens, the Dale, sylvan Corber, or, by an extraordinary effort, to reach occasionally the ruins of the Temple of Solomon; and too rarely do you court the breezes of the hills beyond.

Thus, places out of the beaten track are little known, and the castellated grandeur of Blackwell Dale, the fantastic hills and pretty valleys of the Dove, and the wildly picturesque moors, are not appreciated as generally as they deserve.

Goyt’s Clough, however, to which you are hastening, is about four miles west of Buxton, on the moors, the river Goyt and one of its tributary streamlets gurgle merrily along its sides, and meet at its base.

You go the best and nearest way, taking the Macclesfield Road to Burbage, through the Toll-gate on the Old Road with the independence of pedestrians, past the Level Colliery, pausing on the railway bridge, and turning round to gaze from the hill of millstone grit to the quarries of mountain limestone in the sides of Old Grin, far down into the valley, across the shinning fields to Buxton, to Fairfield, and beyond, until the whole scene is photographed on memory; then, through the gate on the right, ascending the hill, crossing a large field, taking off a corner of the plantation before you, climbing the next style, bring you on the heather – forbidden ground! – and you keep strictly to the path, of course.

Presently you are startled by the warning voice of an old grouse – “Go, go, go, go, go, go back! Go back! Go, go, go, – go!” – but you go onward, watching the flight of the frightened pack until it sinks in the heather of the distant hill; and you think of the time when, in spite of protection, the grouse will be as extinct as the Pterodactyl or the more recent Dodo, and its place be occupied by flocks and herds, as cultivation slowly but surely creeps over the moors, and substitutes grass for heather.

The grouse recognises in man its bitterest enemy, before whom it must give way; and, therefore, – whether he be a sportsman with a gun, bent on ruthless slaughter; a careful shepherd tending sheep, the plodding labourer, or a peaceful pedestrian with a walking stick – the grouse likes not to see the two-legged monsters, shuns them all, and seeks safety in rapid flight.

And a swift and beautiful flight it is! You thrill with admiration as you watch, and would not stop it for an ounce or two of flesh and a few soiled feathers!

An unusually joyous feeling of perfect freedom animates you as you tread the heather, as “far over hill and dale freely you roam,” which could be little enhanced by the privilege to kill – that sanguinary business you leave to the butcher and poulterer!

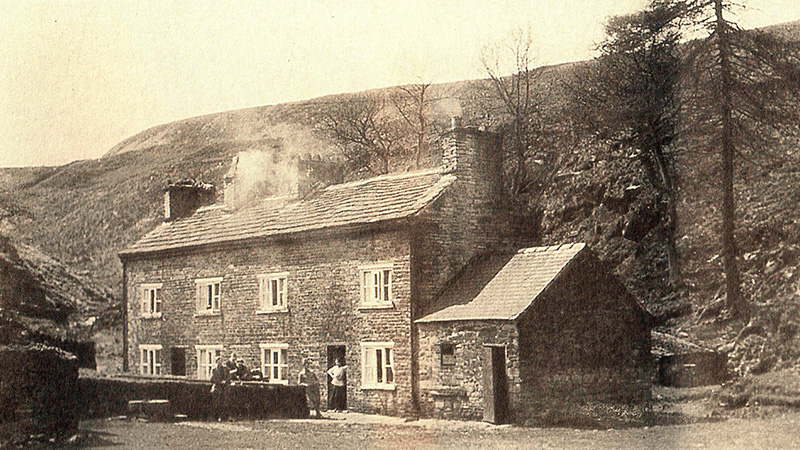

A rugged path soon brings you to one of the little sparkling streamlets mentioned before, and, following its course, you turn round the end of the Clough, see a large building with a cluster of cottages, and have arrived at the end of your journey.

The large building encloses an immense overshot water-wheel, thirty-six feet in diameter, and was used nearly half-a-century – since as a scouring mill, in which the slabs obtained in an adjoining quarry, were scoured to the required surface, and afterwards conveyed to London by Pickford & Co., and there were laid in pavements of some of the London streets.

But, for many years, the mill has been disused, and has been familiar to shepherds and shooters as a half ruin, emblematic of the utter failure of attempt to establish commerce in the domains of grouse and heather.

Now, however, it is in the hands of Messrs. Ellam and Jones, of Derby, who are working the Cawk Mines at Ladmanlow, and who, instead of removing the raw material to Derby, at great expense in carriage, and manufacturing it there, intend carting is from Ladmanlow to Goyt’s Clough, and preparing it for the markets in the old scouring mill.

Accordingly, many tons of ‘cawk’ are already on the ground adjoining, and, at considerable cost, the mill has been adapted to its new business, the cottages are once more tenanted, and little children toddle about the doors.

Messrs, Goodall and Co. have strengthened or made new walls, &c.; and Messrs. Hollinshead and Dakin have protected the wheel from “the pitiless storm” by covering it with a substantial roof of the Clough, and are surprised at the small supply of water which suffices to set the ponderous machinery in motion.

The water is obtained from the Goyt and its tributary to which allusion has been made, and is conveyed along each side of the hill to a small reservoir, from which it is carried by a wooden trunk to the head of the wheel – a cheap and constant motive power.

Inside the mill you notice the arrangements for scrunching and washing the raw material, for crushing it to powder, by three courses; the second slower than the first, and the third than the second, so that the machinery pays its respects and gives a friendly squeeze to every particle.

When started, which will be early in the new year, the machine will scrunch and grind incessantly, night and day, for, if it stop or break, the material sets, like plaster of Paris, “and fastens everything!”

In the next apartment, you find a large leaden cistern, made by Mr. Broomhead, in which the material is steamed or boiled; there are also extensive arrangements for washing it, and a stove for finally drying it; when, in the form of bricks, with the name of “barytes,” it is ready for the market, and is extensively employed in the manufacture of paint.

Adjoining this apartment, you find a boiler, for generating steam for the above-mentioned cistern, fitted by our local engineer, Mr. John Bramwell, and, in another room, is a weighing machine.

Coming out of the building, you survey the wild and lonely valley, the calm silence of which will soon be disturbed by the incessant clatter of machinery; the ‘plant’ looks like the ‘fixin’ ‘of some adventurous yankee in the wastes of America; and the patches of grass, reclaimed from the heath, foster the notion.

You ask a workman from Derby how he likes living at Goyt’s Clough, and with a comical shrug he tells you he has lived there eight weeks, and has in that time “walked sixty-four miles to get shaved! And been lost once on the moor!”

This brings a hearty laugh from all present, and gives a notion of the social difficulties of the situation. Commercially, however, the situation has many advantages, and the probabilities are entirely in favour of the complete success of the spirited undertaking.

The shades of evening gave a deeper hue to the heather, and made the hills appear larger, ere we departed, retracting our steps homewards, with engineers, slaters, and masons, across the silent moors, by the light of the moon and innumerable stars in a clear and frosty sky.

Quick links…

Goytsclough waterwheel #1

Goytsclough paint mill

Goytsclough stone quarry

False assumptions…

I assumed – because of its size – that the waterwheel would have been a ‘breastshot’ type, where water is fed into the buckets at mid-height. But the writer says it was an ‘overshot’ type, with water flowing over the top of the wheel.

Because of its location, I assumed that the waterwheel was part of the paint mill, and not associated with the nearby quarry. But it seems that it was built for the quarry, around the early 1800s, and then fell into decay following the quarry closure. It was put back into action when the paint mill opened in the mid 1850s.

I assumed that the paint mill crushed stone from the Goytsclough quarry to extract the baryte. But it seems the mineral-rich stone, known as cawk, was transported here from nearby Ladmanlow.

One thing I still can’t work out is how the mill lade connected to the Goyt, since the narrow water channel seems to end at the road, which is quite a lot higher than the river at this point. I wonder whether there must have been a steam-driven pump to force water up to the lade. If anyone has any thoughts, please send a message or leave a comment below.

Now there’s a phrase! I’m just off out to “court the breezes of the hills beyond” with Ted the dog 🙂