Above: Goyt’s Bridge – which now lies under Errwood Reservoir. The 20-page A5 booklet was published in the late ’70s.

Goyt Valley by Roly Smith part 1

I recently came across a small booklet called ‘Goyt Valley’. Written by Roly Smith and published by the Peak District National Park, it’s a concise natural and social history of the valley, and provides some fascinating information. The National Park have kindly allowed me to reproduce it here. I’ve split it over two pages. Click on any link below to read that chapter.

Introduction

The Goyt Valley, in many respects, represents the Dark Peak in microcosm. This gritstone valley on the western edge of the Peak District National Park exhibits in the four miles of its upper section many of the most typical features of the northern, eastern and western parts of the Park, where the dark, brown grit is the dominant rock.

Here is found high moorland, woodland, river and valley scenery with the man-made additions of the twin reservoirs of Fernilee and Errwood.

The character of the valley has changed considerably over the years. Before the reservoirs were built, a thriving farming community, a gunpowder factory, a paint mill, a Victorian mansion, and a railway existed. It retains this aura of faded Victorian elegance; an impression heightened by the romantic ruins of Errwood Hall, surrounded as it is by banks of rhododendrons.

But now, most forms of human habitation have vanished, leaving a valley that is visited by thousands every year but which, paradoxically, remains uninhabited.

In 1970, the Goyt Valley was the scene of a weekend traffic ban experiment by the Peak National Park, the Countryside Commission, and Derbyshire County Council. Its success has given the Goyt new found fame as an example of a solution to the clash between pedestrian and motorist.

How the Goyt Valley was formed

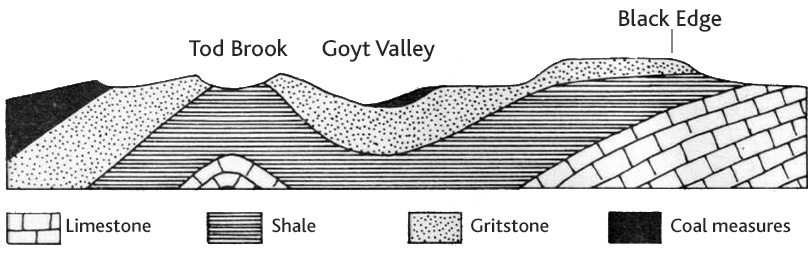

To the geologist. the valley is a syncline – or a downward fold in rocks.

The story starts 280 to 350 million years ago when layers of mud, silt and sand were laid down in a shallow sea from a great river flowing from the north. These were later compressed over millions of years to become shale and gritstone and later still, tilted and folded by earth movements to form the Goyt syncline.

The small traces of coal found in the valley are the remains of vegetation which grew in the swampy delta of that long-forgotten river. Over the ages, the level of the seas rose and fell; sometimes it was deep enough to form shale, at others, it filled up to form a huge delta. This is the reason for the alternate shale-gritsone lavers in the valley.

Geological Section from west to east

Successive Ice Ages sculptured the exposed shales and grits and, later stil, the River Goyt started to carve out the valley as we see it today.

The Goyt rises on the moorland slopes between Whetstone Ridge and the Cat and Fiddle Inn. It flows through steep, rocky “cloughs” and is joined by other tributaries, like Berry Clough and Shooters Clough, to be dammed to form the Errwood and Fernilee Reservoirs. Then the river flows on through Taxal and Whaley Bridge to eventually join the mighty Mersey near Stockport.

Natural History

The special geological and natural history features of the valley have resulted in much of it being designated by the Nature Conservancy Council as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (S.S.S.I.).

Oak and birch woodland once covered all but the highest moorlands, but about 2,500 years ago, the climate became wetter and cooler, and the upper limit of the woodland retreated to be replaced by grassland, heather and bilberry. Sheep grazing also prevented the growth of trees, but old oak, pine and birch woods (known as relict woodland) still remain in places in the valley.

In the valley itself, the moorland has been largely replaced by “improved” agricultural land, but on the high moors which enclose the head of the valley, peat, heather and bilberry dominate the scene.

Moorland

Vegetation on the moors is influenced by their management for sheep and grouse. The heather is burned in rotation to encourage new growth which provides food for both. Other common plants are the cotton grass, the crowberry, and bracken in the cloughs. Coarse grasses, such as nardus, are also common on the moorland slopes.

Voles, hares, rabbits and foxes inhabit the moors and bird life is dominated by the red grouse. It is the only British game bird natural to this country and is only found in the British Isles. Carrion crows and kestrels hunt over the moors: while skylarks, meadow pipits, whinchats and ring ouzels are often to be seen.

Woodland

In the relict woodland areas, various types of fungi thrive and foxgloves inhabit the edges. The impenetrable conifers of the newly forested areas shade all ground cover out of existence, but rosebay willow herb and brambles occur at the edges.

Most woodland mammals are nocturnal, such as the fox, badger, hedgehog and long-tailed field mouse. Not so shy are the ubiquitous grey squirrels, often seen near car park litter bins.

Insect-eating summer visitors, like the redstart, make bird watching in the woodlands an exciting pastime. Resident birds include the jay, magpie (locally named pienet), tree creeper, goldcrest and wren.

Reservoir

In the lower regions of the valley, and round the reservoirs, short turf resulting from years of sheep grazing is the main habitat. Heath bedstraw and tormentil are common plants, and attract butterflies in summer.

Errwood Reservoir is stocked with trout every spring, although some trout do breed naturally in the streams.

The old drystone walls provide cover for wildlife like stoats and weasels, which hunt rabbits and shrews.

Among the birds commonly seen in this area are the lapwing, wheatear, yellow and pied wagtail, dipper, mallard, common sandpiper and swallows and martins.

Farming

We have to go back to around 3,000 B.C. to find the first Goyt Valley farmers. These Neolithic people were partly responsible for the moorland areas as we know them today, because they were the first to start felling the trees which once grew on the higher areas.

Elm leaves for example, were extensively used for fodder for cattle and sheep, and numbers of trees were selectively felled for this purpose. Others were felled to clear land for pasturage.

Later, the moors were burned and drained, as evidence of charcoal in the peat dated at 1300 A.D. indicates.

At the height of its agricultural prosperity, the Goyt Valley supported about 15 farms mainly stocked with sheep. Older farmers however, can still recall the days when large herds of Shorthorn cattle grazed in the fields now drowned under the reservoirs.

The locally-popular breed of sheep, the Derbyshire gritstone, was formerly known as the Dale o’ Goyt — an indication of the fact that it originated in this part of the Peak. Sheep farming is still the most common form of agriculture in the valley, although its main land use today is as a water-gathering ground for the reservoirs.

Forestry

Apart from the reservoirs, probably one of the most profound changes to the valley in the last 5O years has been the tree planting carried out by the Forestry Commission and the water authority.

The Commission leases a total of 2,341 acres of land in the valley from the North West Water Authority, and has planted up to 50,000 trees per year.

Planting started in 1963, and a steady programme of between 60 and 90 acres was achieved each year. The ground was at first considered mainly suitable for pines, and Corsican pines, Scots pines and lodgepole pines were planted initially, along with a limited number of other species. The coastal lodgepole variety — a native of North America — was discovered to be the most satisfactory for the conditions, and now forms the main species of the Goyt Forest.

Groups of lodgepoles, among various other firs and deciduous species are planted along the western side of the valley above the Errwood Reservoir, contrasting strongly with the more mature conifers on the western bank of the Fernilee Reservoir.

The water authority has made smaller, landscaped plantations of conifers and deciduous trees on the east side of the Errwood Reservoir, around the sailing club buildings.

The Errwood arboretum — a botanic garden of trees – was a feature of the grounds at Errwood Hall, and contained examples of trees brought back from abroad by the Grimshawe family in their ocean-going yacht.