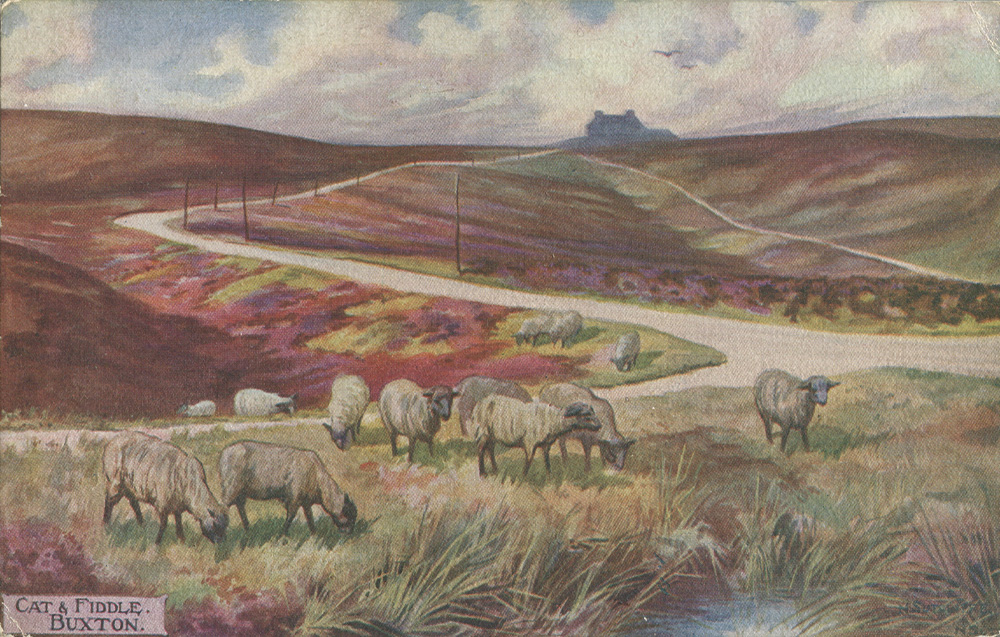

Above: A postcard view of the Cat & Fiddle that looks like it could have been taken in the 1950s – when Crichton published his book.

I’ve circled the famous cat and fiddle carving which in those days lay above the door. Today it’s incorporated into the new porch.

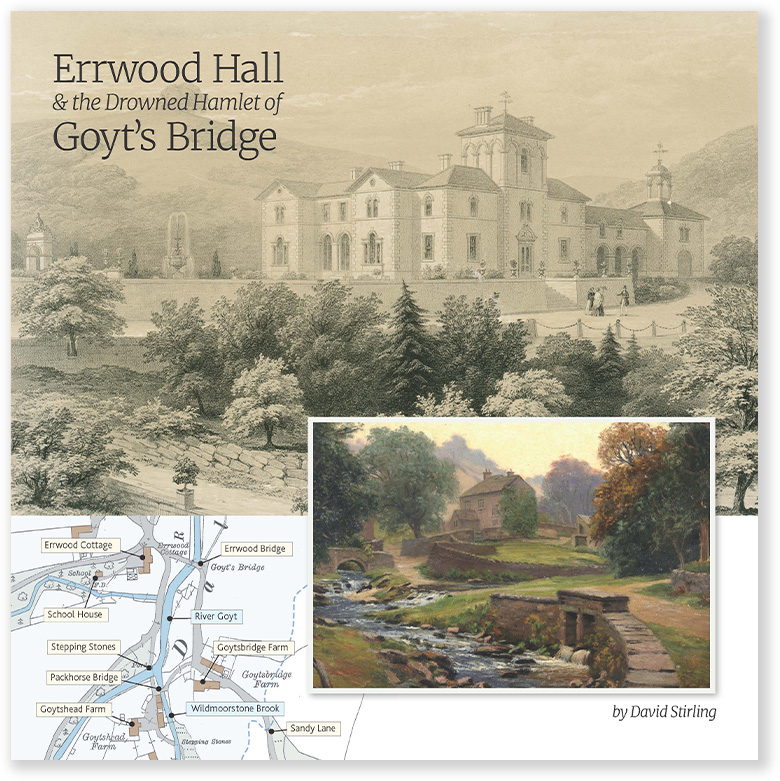

I recently posted an extract from Crichton Porteous’s ‘Portrait of Peakland’, published in 1963 (click to view). This complete chapter, headed Goyt Recollections, is from an earlier book of his titled simply ‘Peakland’ published in 1954.

It includes some fascinating detail about the Goyt Valley, Errwood Hall and the people who both lived and worked in this unique landscape in the time between the construction of the twin reservoirs – Fernilee in 1937 and Errwood in 1968.

It’s fairly long so I’ve split it into three parts. (The text is Crichton’s but the photos and captions are mine.)

Above: Known as ‘the Thomas Hardy of Derbyshire’, Crichton (1901-1991) wrote that “there is more variety and beauty in Derbyshire than in any other county”. View his Wikipedia page.

Four things are remarkable about the Cat and Fiddle Inn near Buxton: its isolation, the bleakness around, its height above sea-level, and the grin on the face of the stone cat which sits fiddling over the porch.

Before Fernilee Reservoir in the Goyt Valley was made it seemed obvious that this cat must be a Cheshire one, because the River Goyt was then the county boundary and the inn was well within Cheshire.

When the boundary was adjusted shortly before the war, a considerable slice of Cheshire west of the Goyt was transferred to Derbyshire, which perhaps gives a little more semblance of truth to the old tale that the cat was not a Cheshire one, but the pet of a Duke of Devonshire, who, being fond of solitude, used to drive up here with his cat and a fiddle.

Unfortunately, the fact is that the cat in the name may not have been an animal at all, but possibly a man, and possibly a game. The man suggested is Caton Fidele (Caton the Faithful), once Governor of Calais, who is said to have retired to Buxton. An old rhyme says:

A hillside man, fond of fresh air,

A house then built, the prospect fair,

For sale of ale, and wine, and mead,

And wondrously he did succeed.He dreamed one night of that doughty knight –

Caton le Fidele – and of many a fight;

Then, waking, said: “His name I’ll give

My house – ‘Caton Fidele’- while I live.’The country folk were puzzled sore,

The name they read it o’er and o’er;

At length they said: “Hey, diddle, diddle,

Why, sure, it must be ‘Cat and Fiddle”

Others suggest that the “cat” was the game of trap-ball, so that the inn name really only suggested pleasure and music. The obvious comment is that games and music must often have been very welcome here, especially on snowy nights when travel was by coach or on foot, for more isolated-looking spot it would be difficult to find.

The road by which the inn stands is nearly the highest turnpike in Britain, two in Durham only being higher, and two in Scotland. The two Durham roads are unknown to me, but the two Grampian ones – from Braemar to Blairgowrie and from Braemar to Loch Builg – look no more desolate than this in the heart of England.

Above: The Cat & Fiddle after a snow storm in 1919.

To see the country around the Cat and Fiddle at its bleakest, go after snow when thaw has set in and there is ice and water about, and some of the heavy wagons that use this route are stranded. A penetrating low mist adds its gloom, and it is difficult to realise that when conditions are better this is as busy a road as many in industrial Lancashire.

The Cat and Fiddle Inn is unremarkable of itself – a plain, bluff building, for this is no site for an ornamented affair. Yet many persons, having heard so much of it, are disappointed when they see it, and wonder about its renown. A notice on an outbuilding gives the altitude as 1,690 feet, but how high the inn stands is not most vividly appreciated just there.

Every visitor should walk 250 yards down towards Macclesfield, and where the road curves leftward pass through the gap in the wall beside a single stone gatepost and continue forward up the grassy metalled cartway to the brow – only another 250 yards or so – for from there a splendid panoramic view south, west and north is revealed.

Above: Looking south from Shining Tor with Shutlingsloe – known as the Cheshire Matterhorn because of its distinctive shape – in the far distance. And the road between Buxton and Macclesfield snaking below.

The fine conical point southward is Shutlings Low. It is said that when the atmosphere is right the Wrekin, fifty miles away, can be seen south-westward. West lie the Mersey Estuary and the mountains of Wales beyond the Cheshire plain.

For a wider view still, keep along the same track – probably a pack-horse route – swinging rightward along Stake Edge to the summit. From there half of wildest Peakland north-eastward is added to the view.

It is a fine spot for a view-finder or indicator, and for a warm day no nicer entertainment can be imagined than to lie on the moorgrass with bilberry tussock for backrest, identifying the ridges and summits beyond and beyond into the distances.

Over the Goyt Valley lie Combs Moss, Rushup Edge, Mount Famine and Kinder Edge – their names alone, as each one is identified, bringing up happy memories, perhaps, or romantic fancies.

It does not matter whether one has been on them all or not; just to see them piled up and serene in the soft glaze of sunlight is enough. And with the views give me the call of the curlew – “one of the most lovely sounds in nature” – and I am content.

Although the Cat and Fiddle Inn cannot be seen from this point, knowing that it is so close one can there fully appreciate its high-upness in the world, and one returns to the main road with an added respect for the person who ventured to plan hostelry in such a place.

The Cat and Fiddle is the second highest full-time inn in England, second only to Tan Hill, in Yorkshire, a mere thirty seven feet higher. In June 1952 three members of the Rucksack Club walked the 120 miles from Tan Hill in two days, leaving the Yorkshire inn on a Thursday at 3pm, the first man reaching the Cat and Fiddle at 9pm on the Saturday.

Tame sheep are a feature at the Cat and Fiddle, approaching every car that stops, and even stepping inside after tit-bits if given chance.

Above: A view of the Cat & Fiddle on the far horizon with some of the ‘tame’ sheep in the foreground. The narrow road leading diagonally right from the pub is what Crichton calls ‘the old coach road’. This was the first turnpike between Buxton and Macclesfield and was replaced by the present A537 in 1823.

On the opposite side of the road from the inn, a short distance nearer Buxton, is the birthplace of the River Goyt, and its course may be easily followed, making pleasant exploration for motorist or walker, though the walker will see the the way from the inn is back by the road to Buxton to the first road off on the left.

This is the old coach road to Buxton. The telegraph wires still follow this route on much shorter poles than are common, short to catch less wind and snow.

The more modern road looks strange above, marked not by walls or fencing, but by black-and-white guide-posts, and usually busy with speeding motor vehicles, which can be seen rushing as it seems wildly to and fro, as if all going to different destinations, though actually following the twists and turns of the one moor road.

For a short way the River Goyt tumbles happily in a little clough between the two roads, then passes under the old road and winds subduedly under unsightly shale banks, like the spoil banks of a poor coalmine.

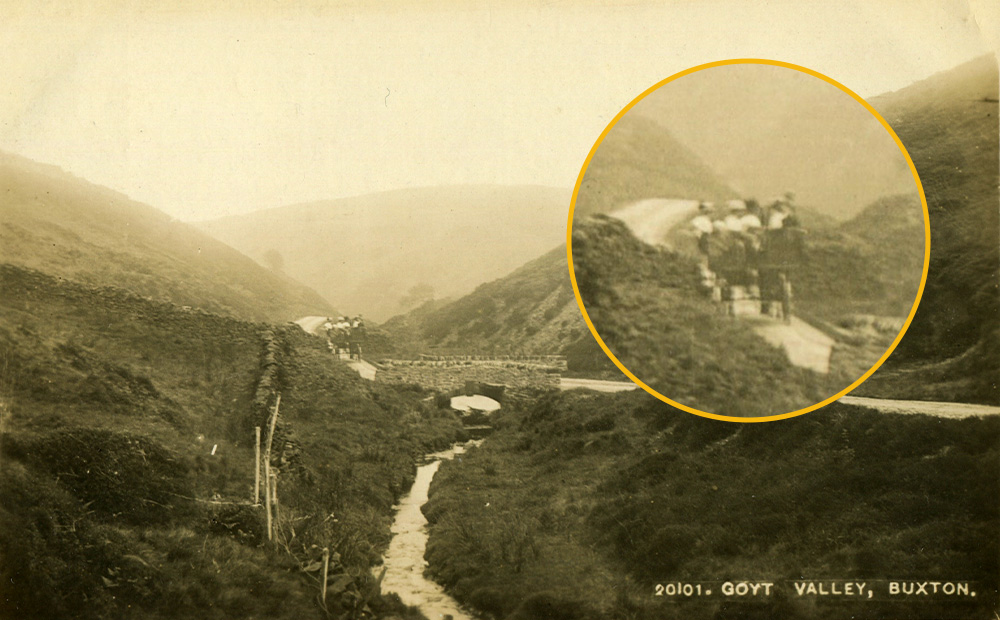

Above: Tourists in the early 1900s being taken along the road beside the Goyt in a horse-drawn carriage, passing over Derbyshire Bridge.

The water soon swings into a narrow gorge, however, and becomes at once a cheery highland stream again, with the narrow road keeping it close company. Before it was tamed under tarmac, this road belonged, as it were, to occasional walkers and the pipits, dippers and yellow and pied wagtails that nest there.

Now too often the solitude is spoilt by cars parked in every gate-place and hollow, and most walkers will find that the more enjoyable way to follow is the path from the Cat and Fiddle already mentioned along Stake Edge and down Stake Side.

This gives only bird’s-eye view of the upper length of Goyt, but brings one to the valley road on its prettiest part, running through open woodland, and not many yards from Goyt’s Bridge, which is as far as cars can get beside the stream.