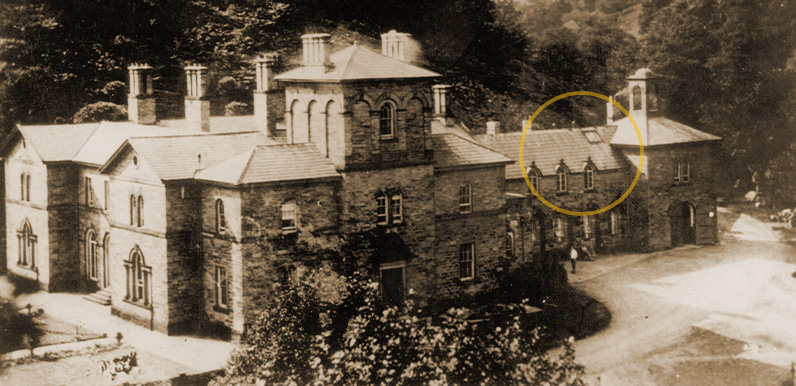

Above: This view of Errwood Hall from the other side of Shooters Clough provides a good idea of the layout. I’d guess it dates to the late 1920s.

I’ve circled where we now think the Catholic chapel may have been situated, rather than the top storey turret.

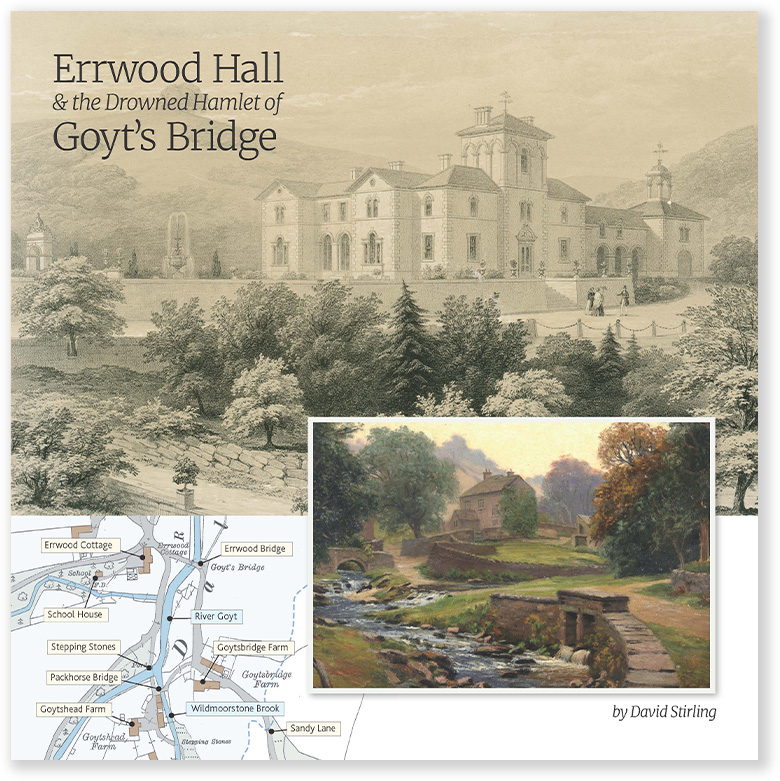

Catherine Parker-Heath is Cultural Heritage Officer for the South West Peak, which includes the Goyt Valley, and is responsible for creating the new augmented reality app (view previous post). Designed to bring the ruins of Errwood Hall to life, it’s still very much in the early stages. One of the first steps is to try and identify the room layout.

Catherine was hoping to find detailed plans of the hall before it was demolished. But United Utilities – the owners of the land – have been unable to discover anything in their records. And neither Stockport Records Office, nor Buxton Museum, have anything in their collections. So working things out is going to mean a lot of informed guesswork.

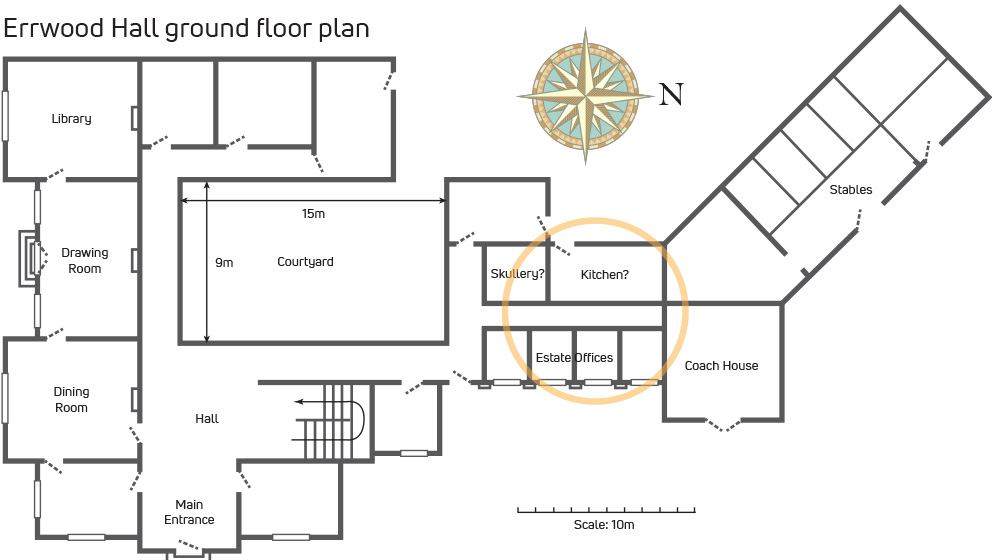

Above: Plans drawn from measuring the ruins in 2004 (click to enlarge). I think the room captions were added later, and apart from the stables and coach house, they were educated guesses. The orange circle shows where we now think the chapel was situated, on the top floor (see below).

One major feature Catherine still isn’t sure about is the central courtyard, which seems a waste of space and wasn’t mentioned in any contemporary sources. It would also have been unusual in a Victorian country houses of this size. Although it may simply have been due to the Italian heritage of the architect, Alexander Roos. Catherine says:

“The only firm evidence we have describing the interior of the house is a report of a visit in 1883 (click to view). And the 1930 auction catalogue detailing the contents of each room (click to view).

“It’s likely that the rooms described in the catalogue would have been written in the order that people viewed them – going from one to the next in rotation. Old photos show the number of windows in many of the rooms. So the number of curtains listed may also be relevant.”

This is the order of the downstairs rooms listed in the catalogue:

- Study; 1 pair curtains.

- Small sitting room; no curtains mentioned

- Entrance hall

- Library; 3 pairs curtains

- Billiard room; 2 pairs curtains

- Drawing room; 1 pair curtains

- Dining room; 1 pair curtains

- Main staircase and landing

Catherine is hoping that others may be able to help with this research, or simply offer an opinion. So if you’re interested, please leave a comment below, or get in touch using the contact page.

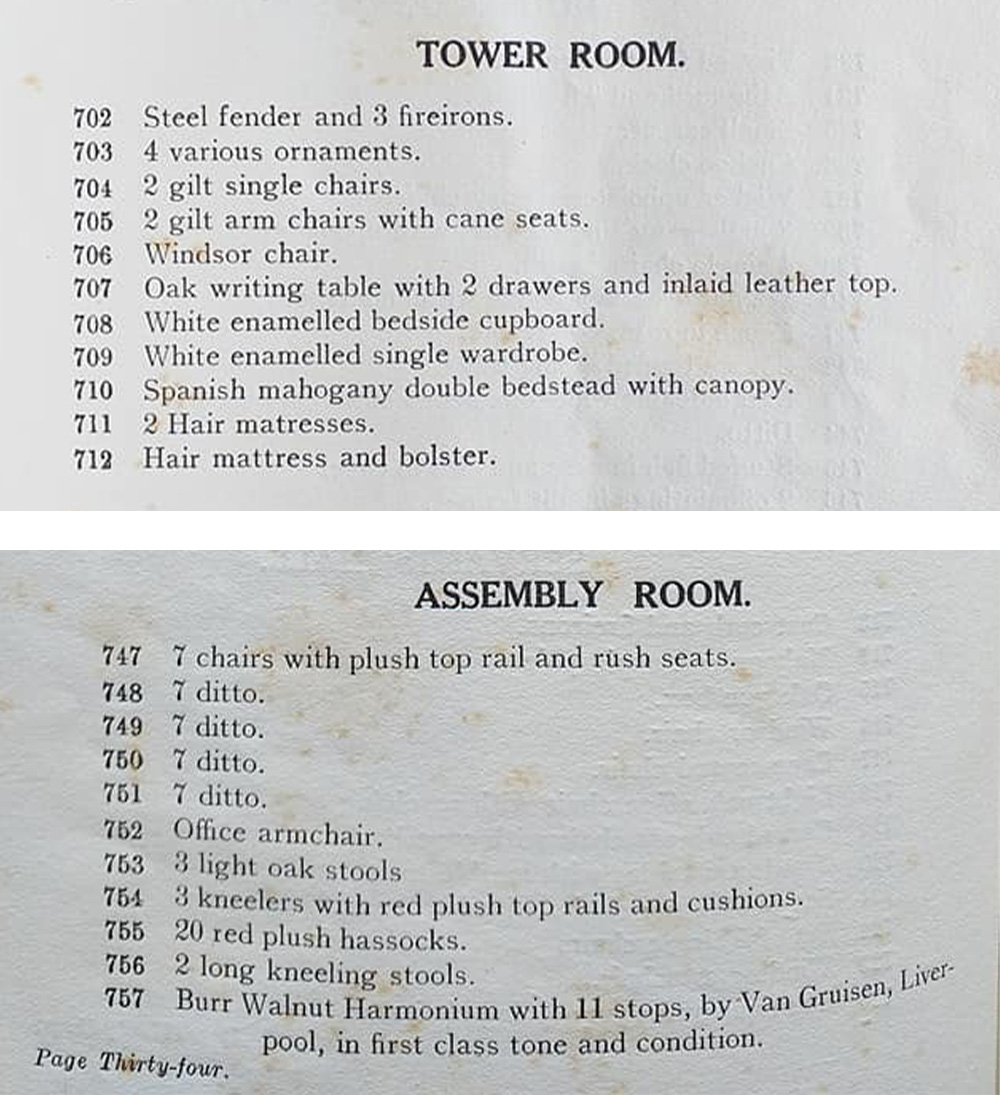

Above: These entries in the auction catalogue (click to enlarge) show that the Assembly room would most likely to have incorporated the Catholic chapel – rather than the Tower room which probably served as a bedroom.

The Catholic chapel

One result of Catherine’s investigations is that she thinks the chapel at the hall isn’t where everyone assumed it was – at the top of the turret. The visitor in 1883 writes:

By the kindness of the benevolent owner we are able to give a few items respecting some of the most noteworthy rooms, and their appointments. Attached to the hall, and in fact, forming part of the building, is a very handsome room, fitted up as a chapel, for the use of the family and servants, and the few inhabitants of the neighbouring farmsteads and cottages to celebrate divine service.

Catherine believes that the turret room would have been part of the private residential area. It’s described in the catalogue as the ‘Tower room containing a double bed’ – so it’s unlikely that local farmers and their families would have been allowed into it.

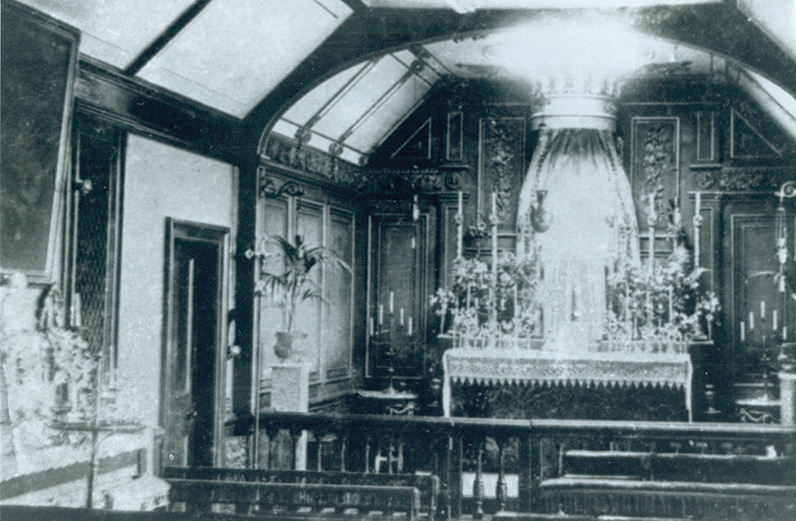

The photo showing the interior of the chapel (above) appears in Gerald Hancock’s ‘Goyt Valley Romance‘ captioned ‘The private Catholic Chapel inside Errwood Hall, located in the upper storey at the northern end’. So Catherine thinks it’s most likely to be what the catalogue describes as the ‘Assembly room’.

The catalogue entry for this room includes five rows of seven chairs with plush top rail and rush seats, as well three kneelers and a harmonium organ. Which sounds very much like a chapel. And since Gerald says it was at the northern end of the house, it looks likely that it was the room circled at the top of the page, and on the outline plan.

It’s a great pity Catherine hasn’t managed to locate a detailed plan of the hall. Particularly to confirm whether the central area was an open courtyard. It would make creating the app a lot easier.

Page update, 23rd March 2022: Dave has just forwarded me this photo of Errwood Hall which seems to confirm that there is an open courtyard in the centre of the building (click to enlarge).

The staircase of the hall was in the main entrance hall, rather than in a separate stair hall as shown on the plan. Two of the treads of the staircase can still be seen on the right hand side of the entrance hall. Many more are likely buried under the rubble infill which must be between three and five feet deep at that point, the floor level of the hall being approximately level with the front doorstep.

The staircase was a broad stone cantilever staircase with wrought iron balusters, and the place where the balusters were leaded into the outer edge of the steps can just be made out on the visible treads. I suspect that the space shown containing the staircase in the above plan was linked to, and part of, the room immediately to the east of it, making one large room to the right of the entrance hall.

Its location close to the kitchens would suggest this room was the principal dining room (by the 1830’s architects had figured out the advantage of having the dining room close to the kitchen to prevent food arriving at the table cold!).

Not all houses had the kitchen close to the dining room. Attingham Park near Shrewsbury had the kitchens nearly 25m away from the dining room, and in the basement, while the dining room was on the ground floor.

Yes, it’s true that many large country houses had their kitchens remote from the dining room, but most of the grand houses of that type are rather earlier than Errwood Hall and Attingham in particular was completed a full 50 years prior to Errwood being begun. By contrast Alton Towers, which was being extensively rebuilt at about the same time as Errwood was being constructed, was altered so that the kitchens were much closer to the dining rooms than they had been.

The reason kitchens were previously kept remote from the main rooms of a house was partly to do with fire risk from the large fires needed for cooking and roasting, and no doubt the associated smells of cooking over open fires, but by the time Errwood was being planned this was no longer such a big consideration as coal fired ranges were then the norm, which were much safer, and the benefits of properly hot food for dinner were beginning to outweigh the much reduced fire risk.

Also, Errwood was probably not a tenth the size of Attingham, so would have far fewer staff to run it. In these smaller houses, practicality tended to be more of a consideration when laying them out. A fairer comparison might be made with the large villas that proliferated in the Victorian era. Of course, we’ll probably never know the truth of it, and my comment previously was more made to highlight the fact that the main stairs are misplaced on the plan above, and to propose an alternative possibility for the space they are shown to occupy on the plan, which I believe is reasonably likely given the conventions of early victorian architecture.

I thought this link might be useful. It’s all about the history of Errwood and who lived there.

An archaeological excavation should confirm if the ‘courtyard’ was indeed that. It could also have been a single storey dining hall or ballroom with a skylight ceiling.

Obviously this won’t be free. The stone infill being removed completely would offer more insight into many aspects too. Maybe one day.