Above: I’ve often wondered about these dark deposits on the exposed hillside beside the road from the Cat & Fiddle to Derbyshire Bridge.

It certainly looks like coal, but if it is, why hasn’t anyone carted it away to warm their homes in this exposed part of the Derbyshire/Cheshire border?

One of the joys of working on this website is that there’s never any shortage of interesting things to discover. And in many cases, one topic leads to another. Which is how I came to start researching the history of coal mining in the Goyt Valley.

I’d been reading a book on water mills on the Derbyshire Wye to see if I could work out how the various water features fed the giant waterwheel at Goytsclough. I noticed it was written by someone who lives fairly close to me in Buxton, Alan Roberts, so decided to get in touch to see if he might be able to help.

Unfortunately, Alan couldn’t add much to the facts I’ve already discovered about the waterwheel. But it transpires that he’s also something of an expert on coal mining in and around the Goyt. And has co-authored a book called ‘The Coal Mines of Buxton’, which I’ve found fascinating reading.

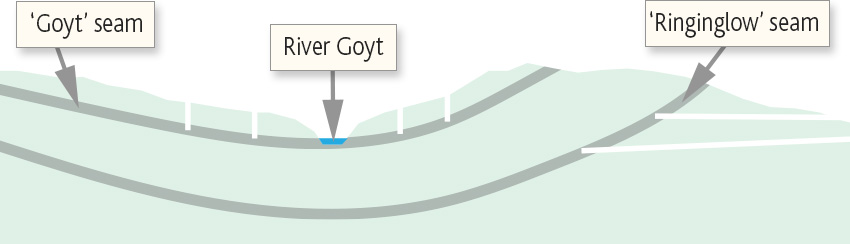

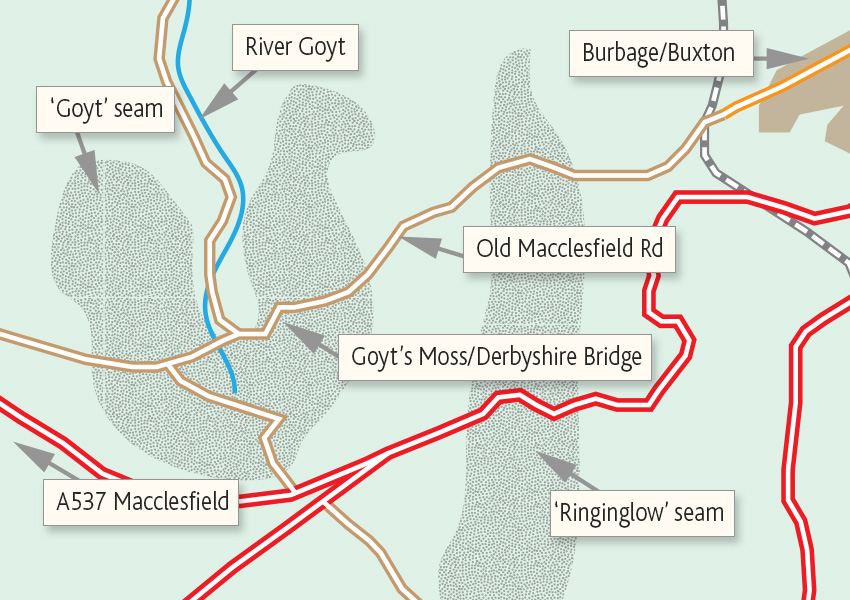

The two diagrams below are based on illustrations from Alan’s book.

Above: Alan’s book, The Coal Mines of Buxton, is available from Scarthin Books in Cromford. Used copies are also available on Amazon.

Above: There are two coal seams in an area stretching from Burbage, on the southern outskirts of Buxton, to Goyt’s Moss (now known as Derbyshire Bridge).

Below: The top layer was known as the ‘Goyt’ or ‘Yard’ seam, and was centred around Goyt’s Moss. Coal was mined from this seam by surface pits. The lower deposit was known as the ‘Ringinglow’ or ‘House Coal’ seam, and was accessed via tunnels from Burbage.

Lime had been highly sought after for hundreds of years as both a soil fertiliser and cement mortar; both vital to feed and house England’s growing population. And with a countrywide shortage of wood, coal was the ideal fuel.

The problem with mining coal from such an inhospitable location was the cost of transport from the mines to the kilns. But with the expansion of turnpike roads in the 1700s, and local railways during the following century, it became a profitable business.

Old maps of Goyt’s Moss and the area to the east show that it was once peppered with surface coal pits. But by the end of the 19th century, most of the seams had become exhausted. The last coal was mined in 1919.

I’ll identify some of the features left on the ground today in a follow-up post. And explain how the industry developed from simple pits to tunnels stretching over a mile through this barren and forbidding landscape.

It would be interesting to see how the old workings have withstood abandonment.

Any fossiliferous specimens/material found in these coal beds?

It’s interesting that many sites, often about the river Mersey, state that the Goyt starts at the reservoirs, it makes you wonder what they think fills them.