The pair enjoyed Whaley Bridge, but were less enthusiastic about the towns and cities just a little further north, particularly the pollution of the River Goyt;

“At present the Goyt at Whaley Bridge is child-like in its innocence and clearness and careless prattle; but it does not proceed much further on its voiceful, vivacious path of poetry and purity before its young life is fevered with factory filth, and, black and reeking, poisoned and polluted, it creeps past New Mills and Stockport to crawl feebly – a liquid leper – into the Mersey. Such are the triumphs, my masters, of this noble nineteenth century!”

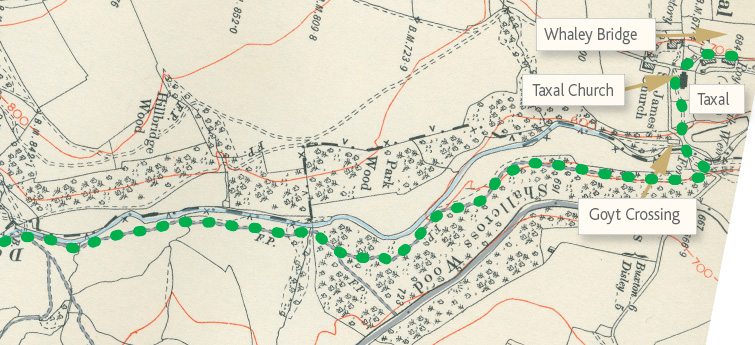

In his wonderfully florid style, he tells of his walk, accompanied again by his ‘Young Man’, from Buxton down to Goyt’s Bridge, and then north along the left bank of the Goyt, past the Gunpowder Works and Taxal Church, to Whaley Bridge, returning by train…

“Oh, mind ye, love, how oft we left

The deavin’ dinsome town

To wander by the green burn-side,

And hear its water croon?

The simmer leaves hung ower our heads,

The flowers burst round her feet;

And in the gloamin’ o’ the wood

The throssil whistled sweet.”

MOTHERWELL.

A Frenchman of genius maintains that the odious climate of England is an overbalance for her good constitution, and that, considering how servile the free-born Briton is to skyey influences, the sun of the south is in truth well worth the liberty of the north.

But now and again come days that compensate us for all meteorological shortcomings, or rather long-comings; that would not be appreciated in a land of perpetual sunny weather, and skies monotonously and intolerably blue; and that make us agree with the shrewd observation of King Charles II, that, with all the imperfections of our climate, more days in the course of every year could be spent in England in the open air than in any other country in Europe.

Saturday, the 7th of May, this year, was one of these rare days. It brought us the first spring day with the warmth and gladness of summer in it. There was the most shining of blue skies; there was a rare atmospheric clearness that brought distant points out in close details; the sun made luminous with light the tender hesitating green of the new foliage; the birds answered with their music to the sweet idyllic influences of this May-time.

Who on such a day tolerate towns when all Nature was inviting him out? The man, indeed, is not to be envied upon whom the month of primroses has no influence, and whose heart does not put forth shoots of generous sentiment and tender flowers of fancy with the leaves and blossoms that the sun is bringing out upon the trees.

Like the war-worn David in the thirsty Philistine land, the mind of the prisoner in the debilitating town is on such a day carried to the green valley, where the water flashes in the sunlight, and the trees throws leaf-shadows on the sward, and he exclaims with the Shepard-King: “Oh, that one would give me drink of the water of the well of Bethlehem, which is by the gate!”

No wonder that the prisoner escapes and finds himself rambling out in his beloved Peaks Countrie with the Young Man, the companion of many a romantic rampage. This vivacious venerable joins gayness with grayness, and unites the elasticity, the exuberance, and the enthusiasm of a young Etonian with the wisdom and experience of extended Age.

He is as sturdy and hard as a bluff weather-beaten Debyshire crag, and as blithe and bubbling as a moorland stream shouting and leaping in the light for very joy.

In his innate sympathy with bird-life he might have in a past stage of existence belonged to the bird-world; and if his fortune failed him, he might make a respectable income by giving limitations of the notes of the various birds he can mimic so well as to deceive themselves; just as Thackeray, to whom calligraphy was one on the fine arts, boasted that if all trades were closed to him, he would earn sixpences by writing the Lord’s Prayer and Creed in the size of that coin.

The Young Man and myself had started out for a pilgrimage in the Peak on the previous Saturday, but were driven back by gray skies and gusty rain. What a difference the sun makes in a picture!

A week before there was no colour anywhere; drizzly and dreary was the day; the hills were blotted out in brooding mists; Buxton seemed a town without hope; a watery gleam that was to be seen in the west, only added to the sombre effect of the day on our emotions.

But now behold! The bright, blithe day, its burning blueness rejoicing us with its sparkle, and mirth, and strong colour. As we ascend the Manchester Road, Buxton in the hollow, shines like a pearl, the sun flashing on white houses and windows is a glare of glittering light.

The uplands by Chelmorton are strangely near; one can see the stones and grass-tufts on the hill-sides, as if there were in intervening distance of several miles. Aerial perspective is lost in the intense light. Every line in the subtle curves of the hills in the west by Axe Edge is drawn in minute detail.

The most beautiful translucent green in creeping over the steep slope of the Corbar woods; but the foliage is very late this year, and there are some trees that will never open their buds again in response to the spring time.

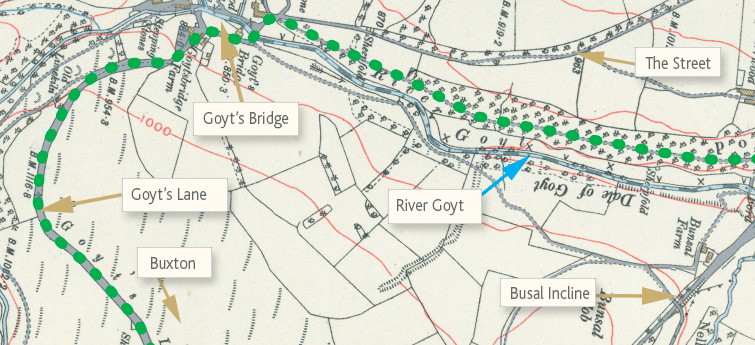

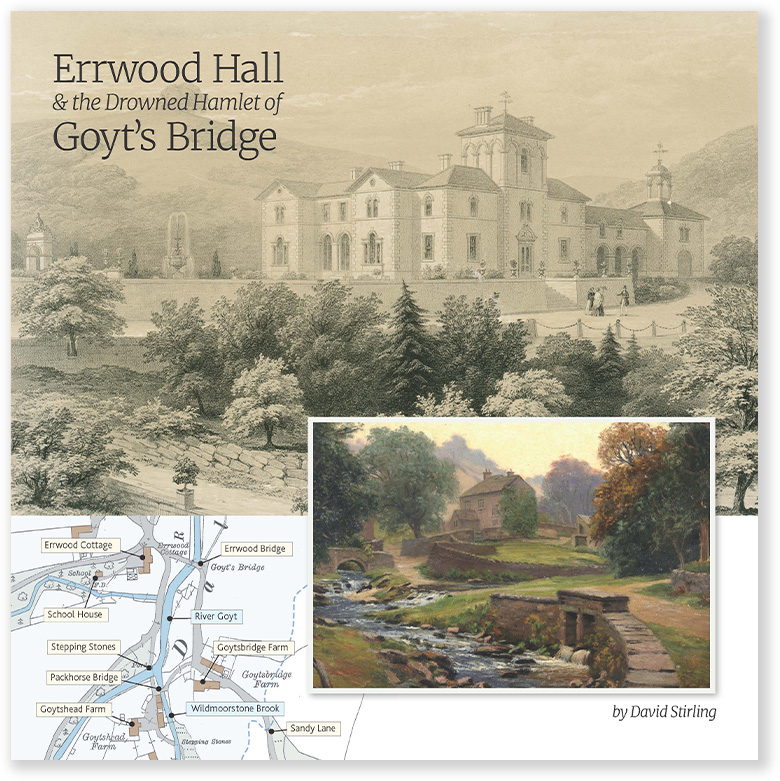

Starting from Manchester Road in Buxton, they forked left down the narrow, undulating lane towards Goyt’s Bridge.

At the top of the Bunsal Incline, just past the engine house which hauled trains up and down the steep slope, they turned left down Goyt’s Lane to Goyt’s Bridge.

Here they they turned right, crossing the Goyt at Errwood Bridge, and followed the footpath alongside the left hand bank of the river.

On a previous occasion the Young Man and the present writer explored this narrow secluded dale. We then pursued it up stream from Goyts Bridge to the Axe Edge moors above Buxton, where the voiceful river rises. And a wild, picturesque, lonely ramble that is.

“Let us be silent,” pleads Emerson, “that we may hear the whispers of the Gods.” In the upper solitude of the Goyt Valley you might almost listen to their talk. But to-day we are intent upon keeping company with the river downstream to Whaley Bridge; and the Y.M. is confident that the walk will reward us with a wealth of pictures that would detain the most fastidious artist.

We are to keep the river side the whole of the way. The excursion is quite practicable from Buxton within the limits of an idle afternoon. For that matter, indeed, the lover of nature may leave dolorous Derby by the noon express for Buxton, and accomplish without furry or fatigue the walk to Whaley Bridge, and return from thence by train to Derby the same evening. But this by the way.

There is a great deal to be urged in favour of walking down with a river instead of up against it; and that is eloquently expressed by a novelist friend of ours when he writes:

“It is surely more genial and pleasant to behold the river, growing and thriving as we go on, strengthening its voice and enlarging its bosom, and sparkling through each successive meadow with richer plentitude of silver, than to trace it against its own grain and good-will towards weakness, and littleness, and immature conceptions.”

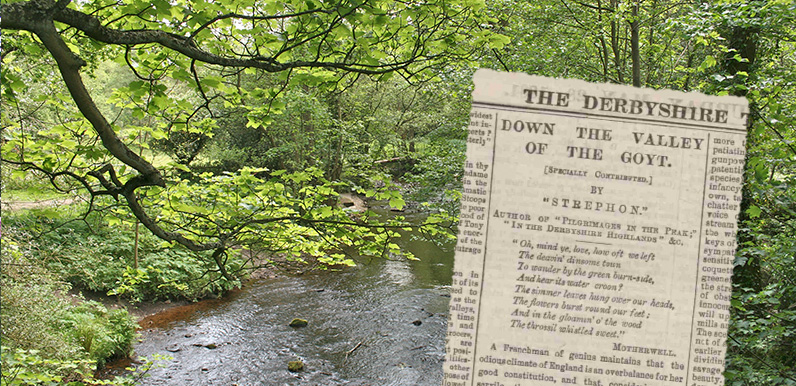

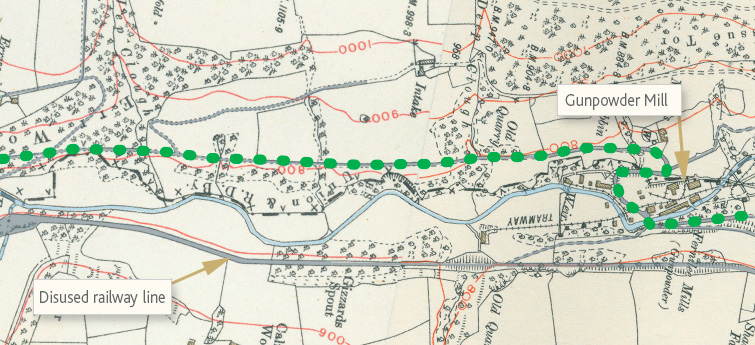

Past the scattered houses at Goyts Bridge, with the trickle of many moorland rills taking their tributary wave to the eager strong-willed river; leaving to our left the wooded slopes that enclose Errwood in investing lines of beauty – with the massy rhododendrons rising in banks of glossy green; with the silver birch – “the lady of the woods” – wearing a veil of lace-like green; with the larches clad in the most vivid emerald that stands out in emphatic contrast with the sad, dark shading of the pines and firs, and the bare black boughs of the tardy oak and reluctant ash; past all these woodland wealth – with restful chords of colour which would have won the enduring love of Lord Beaconsfield with his attachment for sylvan scenery; past an inclined plane of the High Peak Railway; past the isolated Powder Mills a little further on, the scene, despite all the care of manufacture, of more than one explosion, (the Y. M. is expatiating upon the paradox of a parson inventing gunpowder, and of a Sheffield Wesleyan minister patenting a new engine of murder of the torpedo species), with the river Goyt growing up from infancy, and with a winning individuality of its own, talking to us with incessant and innocent chatter all the way.

It crosses the Goyt just before the Gunpowder Mill (the ruins of which now lie under Fernilee Reservoir).

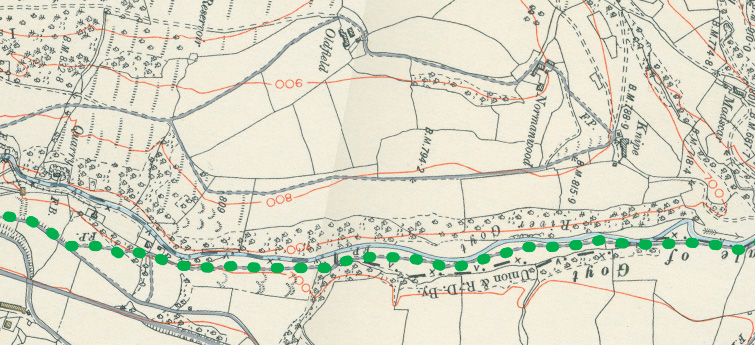

The two friends then followed the footpath along the right hand bank of the river, all the way to Taxal.

The scenery of the lower reaches of the Goyt is not of such a wild character as the upper and earlier portions. Errwood seems to be the dividing place where the landscape loses in sad, savage, poetic wildness, what it wins in sylvan beauty.

Instead of the hungry moors slipping down in declivitous steepness into the water, there are woodland glades with lawns of green, and the broken rocky track gives way to a well-ordered path. Glade after glade of green opens out to challenge admiration with its predecessors.

On the moors above us the heather retains its winter sadness of colour; and the bracken is of a rusty red; but in the valley here the ferns are unfolding their fiddle-head like fronds; and the banks are starred with the little white wood sorrel, with its tender trefoil leaf, with the wood amenone, with constellations of primroses, and a milky-way of cowslips.

The lily-of-the-valley grows wild, but the botanic brigands known as “Field Naturalists” have thinned the growth of this flower. A bank of blue forget-me-nots looks like a patch of fallen sky. The blue-bells are not out yet; and where is the purple-mouthed orchids?

The level stretches of meadowland with the young short grass make the most perfect lawns gently sloping to the water – “sward” – as Mr. Ruskin would write – “smooth as if for knights’ lists, and sweet as if got dancing of fairies’ feet, and lonely as if it grew over an enchanted grave.”

The lady-smock is not yet out, and it is too early for buttercups; but a field of the cloth of gold is not altogether wanting; for there is the golden yellow of the celandine, of the marsh marigold, and of the coltsfoot.

(The Y. M. has much to say on the important subject of coltsfoot beer: A botanic beverage which a past generation of thrifty housewives were wont to brew in the spring-time, which uncorked as clean and sharp and sparkling as the finest champagne, and, moreover, was as miraculously efficacious in its hygenian qualities as those potent pills, mentioned in an American paper, one box of which not only cured the father of a family completely of gout, but also relieved his wife from the rheumatism, his children from the measles, and besides all this, to the amazement of everybody, mended the kitchen stairs!)

But the yellow-beaked blackbird whistles cheerfully in friendly rivalry with a confident redbreast; we have been watching the twittering flights of young wrens making trial-trips on their new wings; the shadows of swallows flittingly fall on the grass; the lark has lost none of his old-celestial sweetness; the wagtails are busy by the water; and on the moors is ever and anon heard the querulous note of the “wanton lapwing,” now getting itself that “other crest” mentioned by the observant hero of “Locksley Hall.”

At the intervals the cuckoo tells the other birds his name. it is the first time we have heard his song this year, and we recall the tender beauty of Alexander Anderson’s aching lines:-

“Two simple notes were all he sang,

And yet my manhood fled away;

Dear God! The earth is always young,

And I am young with it to-day.A wondrous realm of early joy

Grew all around as I became

Among my mates a bearded boy,

That could have wept but for the shame.For all my purer life, now dead,

Rose up, fair-fashion’d, at the call

Of that grey bird, whose voice had shed

The charm of boyhood over all.O early hopes and sweet spring tears!

That heart has never known its prime

That stands without a tear and hears

The cuckoo’s voice for the first time.”

There are plenty of merry little mountain trout in the river pools; and down the stream is a fly fisherman, standing at a bend of the water just where an artist would have placed him for effect in a picture.

We sit down with a long vista of broken river above us on a huge boulder that is cushioned with a marvelous mosaic of mosses and lichens. All around us in the cadence of the current, the talk of the tremulous trees, the caress of the sweet clear air, the stirring of many forms of spring life.

The sky is a pale shining blue, with the glare here and there broken by a line of light cirrous cloud, the moors rise in bold curves against the horizon. It is just a place to dream a long afternoon away with contemplative pipe and a novel by William Black; one of the few writers that will stand the test of reading amid such scenery for he almost approaches in picturesque charm Nature’s own romance.

The Y. M. ceases describing a funny experience at what is known as the “merry meal” by the old farm dames of the High Peak – “a sup o’ tea wi” a sup o sum’at in’t” and we give ourselves up to the poetical influences of the wood and water and distant world. When he takes his pipe from his mouth it is to read aloud a passage from a favourite author which harmonises just now with our own emotions.

“Here no man, however lame he may be from the road of life, after sitting a while and gazing can help feeling that he is refreshed and even comforted. Though he hold no commune with the heights so far above him, neither with the trees that stand in quiet audience soothingly, nor even with the flowers still as bright as in his childhood, yet to himself he must say something better said in silence.

Into his mind, and heart, and soul, without any painful knowledge, or the noisy trouble of thinking, pure content with his native land and its claims on his love are entering. The power of the earth is round him with its lavish gifts of life, – bounty from the lap of beauty, and that cultivated glory which no other land has earned.”

“Sweet,” indeed, as Wordsworth says, “is the lore which to the town-toiler in the hidden meaning of the old mythology of Antaeus always receiving new vigour in his combat with Hercules when he touched the green earth, and only falling in the unequal encounter when taken away from the inspiration of Nature.

The two friends would have crossed the Goyt at the ford, over an old packhorse bridge that has now been replaced by a small wooden bridge.

They then walked up the lane to visit Taxal Church, which they found very unimpressive. Before following the road all the way into Whaley Bridge, and catching the train back to Buxton.

Taxal might almost belong to Joseph Hatton’s “Valley of Poppies,” so moss-grown it is and still. The only life we see consists of a black-faced ewe and her pretty staring lamb; an inquisitive group that made us wish to summon to the spot, instanter, Mr T. Sidney Cooper for him to paint it against the lovely background of hills; together with two children at a farmhouse, with tangled hair and faces whose healthy complexion it would be difficult for a painter to catch, with the young red glowing through the sun-burnt brown.

The Y. M. is never so happy as when he is making friend with little children; and despite the broad expanse of his grey beard his heart must be as young as theirs, for they become instant companions.

The little girl whispers with a face of laughing mystery to her brother, who dives off suddenly, and we are next attracted to his presence by a mocking shout from the topmost window of a grey moss-grown old barn, where the lithe young rascal appears nursing a white long-eared tame rabbit, while the small lady below crows with delight.

The window just frames the picture, and in sooth it is pretty study; but I must lead the Y. M. away, or he will be playing whip and top, flying kites, or dressing dolls, and forget all about his friend, and the fact that Time and the London and North Western Train wait for no man.

A look at Taxal Church, a not particularly interesting building, and no archaeologists would rage against its “Restoration.” There is, however, a splendid old yew in the churchyard, where the good Rector’s sheep are thriving mightily on departed parishioners who have been transferred by the chemistry of Nature from the animal into the vegetable kingdom.

The sheep has his revenge on us after all. We eat him; but a facetious Fate ordains that his children shall eat us. Revenons à nos moutons! There is a subtle law of compensation in Life, and the sheep has ultimately the best of it.

Taxal Churchyard is on the slope of a steep hill glancing over the Goyt Valley. The view is one of the most majestic in the whole of North Derbyshire. It demands the space of a large canvas; how can I crowd it into this little cameo?

It is Saturday afternoon, bear in mind. There is no smoke from the chimneys of the manufactories with which Mammon has dared to affront Nature in her most romantic mood. The crystal clearness of the air brings out the heights in great vigour of outline and “modelling,” and the number of bold hills meeting here in concert supplies almost every shape of mountain form: peaked, rounded, rampart-like serrated.

To the left of the picture, with the Goyt Valley intervening, Combs Moss rises an austere grey moorland bastion, lofty and threatening. The Trophonious-like cave beyond, from whence an express train escapes with a wild scream, is the Dove Holes tunnel on the Midland main line to Manchester; at a more northern point of the same valley, above chapel-en-le-Frith, a delicate mist of the blue smoke, is the Todd-brook reservoir, one of the feeders of the Peak Forest Canal; right across the picture in a pearly haze of heat are Mam Tor and the Castleton hills; nearer at hand in the mellow slanting sunlight Keeles Pike towers over the Whaley chimneys, boldly supported by Chinley Churn, Cracken Edge, and reinforcements of other hills; and then behold!

Standing out blue and vague against the soft sky line, the two haughty peaks of Kinderscout. The reservoir below – mirroring green shores – supplies a peculiar charm in the scenery, a charm which Derbyshire landscapes notably want.

The Peak Countrie is rich in rivers and musical with rills and rivulets; but it lacks lakes. This reservoir below, reflecting sky and shore, looks like a natural more in the beauty of its wild mountain surroundings and in the broken irregularity of its winding shores.

It just serves to show how water would improve Derbyshire scenery. People who have never seen the Alps would instantly compare this view to something in Switzerland. It certainly carries with it the illusion of Cumberland and Westmoreland. Enough that it is in Derbyshire, which need not depend for a pictorial reputation upon comparisons with either the Lake Countrie or the Continent.

The young Man tells a good story he has heard of the late Bishop of Exeter. The vicar from his house at Bishopstowe, overlooked the beautiful inlet of Anstey’s Cove. A lady was one day looking at this prospect from his windows. “Dear me!” she remarked. “How very lovely. It is like Switzerland.” “Yes,” responded the Bishop, “only this has no mountains, and Switzerland has no sea.”

This anecdote, with some collateral detail, has carried us into Whaley, a pleasant walk of little more than a mile. Perhaps we have walked nine miles altogether, in following the windings of the river. The train is almost due that will take us back to Buxton.

Whaley Bridge is a healthy moorland town, which has, however, caught the infection of mills and colliery shafting. The spirit of Pelf* is being pitted against the Picturesque. In a few years, no doubt, “God’s Country” will have been disfigured and degraded into “man’s town” and the giddy Goyt will be sobered into steadiness by sewage; and now the bright emerald grass will pine sickly for a coat or two of green paint.

At present the Goyt at Whaley Bridge is child-like in its innocence and clearness and careless prattle; but it does not proceed much further on its voiceful, vivacious path of poetry and purity before its young life is fevered with factory filth, and, black and reeking, poisoned and polluted, it creeps past New Mills and Stockport to crawl feebly – a liquid leper – into the Mersey. Such are the triumphs, my masters, of this noble nineteenth century!

My thanks to Mike for sending me Strephon’s two articles.