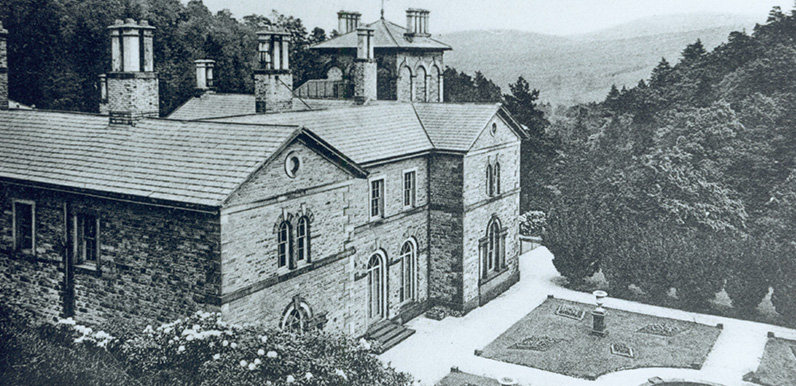

Above: A fine view of Errwood Hall and its ornamental gardens, taken from the path up to the Grimshawe’s hill-top cemetery.

This article is taken from a 1954 issue of the Peakland Magazine, and written by Crichton Porteus. It appears on the Whaley Bridge Historical Group’s website. Reproduced here with kind permission of Norman Brierley.

Behind where the hamlet [Goytsbridge] was is Errwood Valley and relicts of Errwood Hall. The last occupiers were two old ladies who used to drive regularly in a carriage and pair down the Goyt Valley by a sandy road (most of it now under Fernilee Reservoir) to the Long Hill road and so to Whaley Bridge or Buxton.

Between the wars the house was still well kept up (see photo above). Then the sisters died – they were the last of their line – and for a short time the Hall was a hostel for ramblers. At my next visit it was being dismantled because of the reservoir scheme. Contractors had paid a lump sum for what they wanted. The best stone had been taken, the rest left, and none who see what is there now can form any proper idea of the beautiful old home.

It was a double-winged house with a central tower, all standing on a broad terrace looking south. At the east end in the upper storey of a long extension was the private chapel. At the west end of the house a French window gave into a terraced garden.

Wide steps led to the front entrance. Over it was a proud stone dragon, and above the tower a proud metal dragon told the way of the wind. The dragon was the crest of the original Grimshawes. The last Grimshawe, a daughter, was married to a Gosling, and the name became Gosling-Grimshawe. In the gardens was an ornamented stone arch surmounted by bird and a large ‘G’.

Errwood Valley is still noted for the show in spring of rhododendrons and azalea blooms, but the best place to see them from was the upper room of the tower. One almost seemed to float on colour, and the scent coming up with the damp and peacefulness of evening made one think that no place could be more beautiful.

After such memories, to see the raped building at first was pathetic, though now nature has softened the despoliation somewhat. On a quiet knoll behind the hall the private burying-ground had received dependants as well as members of the family.

One stone commemorated a seaman, aged fifty-five, who for thirty years had been captain of Grimshawe’s yacht ; another stone, a Frenchwoman, presumably a governess—a strange place, this wild glen, for her to die in, so far from her native land. The last stone was dated 1911, to a gamekeeper, Pownall, who is remembered to have been very well off, having been left £1,000.

Any tenant or worker on the estate had the privilege of being interred there. Privilege it must have seemed when the estate was flourishing, though somewhat different now – a forgotten place, with crosses atilt, the graves lost under weeds, and the little burying-house, which held a tiny altar and a series of old tiles depicting the Stations of the Cross, desecrated. The whole railed space, when tended carefully, seemed to speak of a very benevolent despotism.

Halfway down the knoll on the side away from the Hall there used to be a row of cottages for estate-workers. The cottages looked on the stream, where the sheltered gardens with greenhouses and fruit trees were. Behind the gardens were the tennis courts, and upstream was the swimming pool.

Above: The well in the wall is still clearly visible today. It provided water to the cottages which once lay at the foot of the path from the Grimshawe’s family graveyard. The photo is taken from Castedge Farm, which is now just a sad pile of stones. The remains of the attractive cottage in the distance are also easy to find, as are the walls which once surrounded the cottage gardens.

The Hall even had its private coal-pit, going a mile and a half diagonally into the hill behind. The Hall took all the lump coal – there was not much – and the rest, poorish stuff, was sold to farmers around at 5d. a hundredweight. If made up over a fire of good coal, it lasted a tremendous time. A yarn is told of a farmer who went to America and when he returned found his fire still in!

A man who worked twelve years for the two last Gosling-Grimshawes told me:

“There wern’a two finer ladies than them nowheer. It did’na matter wheer they were, they’d move ta me. If they saw me i’ Buxton they’d pick me up thay would an’ all! Aa were th’on’y man as worked theer as werna a Catholic. Most chaps went tath’ private Chapel th’ first Sunday they worked theer an’ then ‘ad to keep it up, by As did’na. An’ they ne’er looked daan on me fer it. That’s what Aa liked abaat ‘em.

How far off those days seem! Sad memories and the man who gave them has now been dead a dozen years. But well I recall his: “Yo’ should see th’rhodies theer, lad! Non a few flowers miles on ‘em. Flowers as far as from ‘ere ta them rocks yonder” (indicating quite a mile.)

It was this recommendation that made me go to Errwood first, and was in time, just before the benevolent reign ended. My old friend did not stay quite to the end. A new bailiff had been engaged, he explained:

“Aa knew every yard o’ Errwood—reet up ta th’ back door o’ th’ Cat an’ Fiddle. Aa were working reet up theer, makin’ gaps up so as sheep couldna wander. Yo’ know, if they got aat Macclesfield Forest way, we ne’er saw owt on ‘em agen. They’re aw rogues that way! Any’ow ‘e come up ta me an’ said: ‘Well, John, A’am yo’re gaffer naa.’ So Aa looked at ‘im an’ Aa said: ‘Tha anna. Aa’ll walk far enough afore Aaa’ll ‘ave thee fer mi gaffer.’ So Aa gives mi fortnight’s notice. Aa were gassy then, an’ ‘ad money in mi pocket, an’ in th’ bank, an’ did’na care fer noobody. Th’ old ladies wanted me ta stop, bur Aa wouldna. Aa’m an Englishman, an’ winna be ‘umble t’anybody.”

While the Hall was still occupied the grounds were opened at rhododendron time every spring for years so that anybody might enjoy the beauty. But there was much smashing of bushes and taking of flowers, and eventually someone broke the nose off one of the religious figures that stood in niches in the wall round to the main steps. That was an insult the devout owners could not forgive and all privileges were withdrawn.

After Errwood Hall was abandoned the massed rhododendrons and azaleas became a breeding stronghold of hill foxes, and for many years the keeper from White Hall organised an annual shoot there. Farmers with guns from neighbouring valleys would stand in line across the top of the glen, and men and youths without guns would beat up towards them.

It was a job remembered, pushing through the undergrowth so as not to miss anything, for the rhododendron stems were inextricably tangled and as tough as wire. Sometimes, however, five or six foxes were shot. The last year before the second war a dozen beagles belonging to the High Peak Hunt were used in place of men beaters, but only one fox was put out, a vixen, though.

Goyt’s Bridge without its cottages seems a sad place now for all its remaining beauty. The stepping stones even appear to be gradually disappearing; the pack-horse bridge close by spanning the tributary off Burbage Edge is in much better condition. After coming down the old track off Long Hill, the pack-horses turned sharp right on the lower side of the bridge and went through a ford across the much wider Goyt.

One track then, I surmise, as already said, went up Stake Side, and another followed “the Street,” up to Jenkins Chapel and on to Saltersford. Probably this was the main route by which salt was brought in the Middle Ages from Cheshire into Derbyshire. Motorists who do not care to retrace the route by the upper Goyt must leave the Goyt by this Saltersford lane and will soon come to Jenkins Chapel. It somewhat resembles a barn, but has been a place of worship about 250 years.

Walkers can go on from Goyt’s Bridge beside the river by crossing the stile to the left of the railed-up gateway opposite the entrance to Errwood. They then follow the old carriageway of the Grimshawes. Soon the river sounds on the right die out as the current loses itself in the deeper water of Fernilee Reservoir.

Near the head of the reservoir a steel suspension bridge, connecting as it seems no special place to anywhere else, spans the water, offering a good view northward of the wider end of the reservoir. Erected in 1935 at a cost of well over £500, this bridge is scarcely used in the week.

When Stockport Corporation secured powers in 1929 to build two reservoirs (one still to be made sometime, the dam above Goyt’s Bridge,) the Act of Parliament stated that any public paths interfered with should be replaced by others, and this bridge takes the place of an old ford across the Goyt.